The gimmick-free nature of her music and public image perturbed sexist, unimaginative major-label executives in the ’90s, when the industry was still printing money and every act was expected to break out with the same velocity as Nirvana. All of this made her an outlier in the music industry at large. Over the course of four decades, she has been a pop flavor of the week who reinvented herself as a singer-songwriter a folk-rock traditionalist who refused to posture her way into a self-consciously edgy alternative idiom a woman whose persona isn’t seductive or enraged so much as pensive and, at times, embittered an artist in a youth-obsessed industry who started doing her best work sometime in her late 30s. The traditional narrative around Mann’s career frames her as an aberration. This is the environment that nurtured Mann’s brilliant 2000 album Bachelor No. Largo became an ersatz salon and fostered some of the greatest collaborations of its time. Music-loving filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson and Michel Gondry were in the mix, too.

Flanagan also filled out bills with pillars of LA’s stand-up scene: Zach Galifianakis, Margaret Cho, Sarah Silverman. Owned by Mark Flanagan, a towering Irishman with discerning taste in music, Largo became a haven for the eclectic, sophisticated pop sound Brion championed, played by performers who’d long ago outgrown open-mic nights.

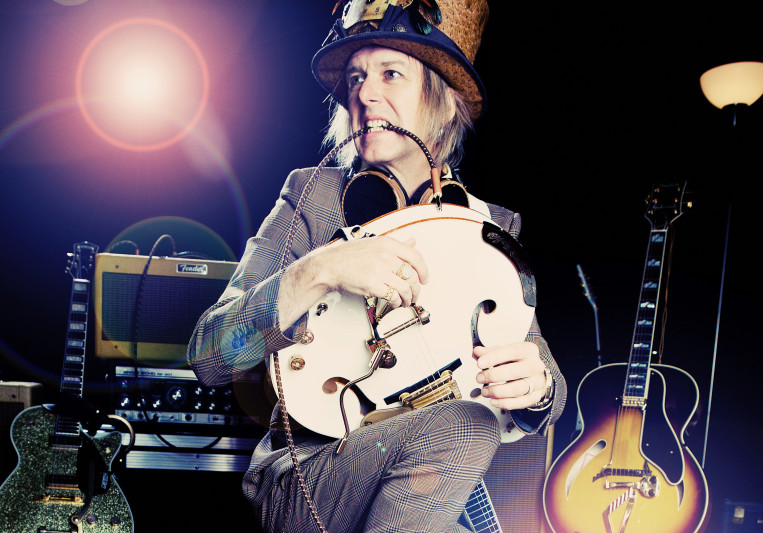

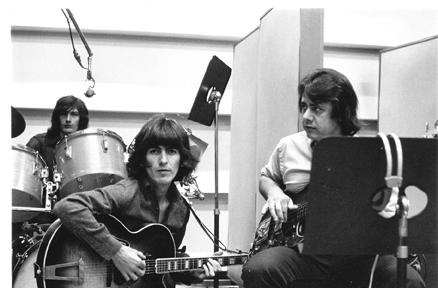

On any given night, John Paul Jones, Jackson Browne, or even Kanye West could appear on the tiny, rug-covered stage. Among frequent guests were some of Brion’s most distinguished collaborators: Fiona Apple, Rufus Wainwright, and Aimee Mann. Every Friday night, seated at a secondhand piano (that at some point acquired a decorative Viking helmet) and walled in by arcane analog instruments, the star producer, composer, and musical polymath put on a show. “Unpopular pop.” That’s the phrase Jon Brion used in 1999 to describe the music scene at Largo, the 120-seat venue in West Hollywood where he ran a weekly residency for more than a decade.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)